The lab at Terray Therapeutics is a symphony of automation in miniature. The robots rotate, sending small tubes of liquid to their stations. Scientists in blue coats, sterile gloves and goggles monitor the machines.

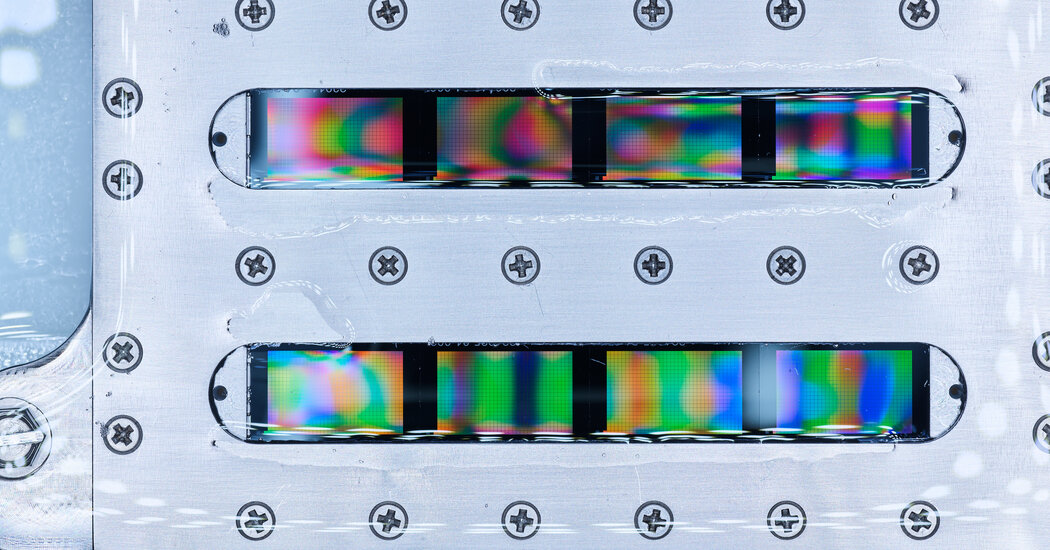

But the real action is happening at the nanoscale: Proteins in solution combine with chemical molecules held in tiny wells in custom silicon chips that are like microscopic muffin tins. Every interaction is recorded, millions upon millions every day, generating 50 terabytes of raw data every day – the equivalent of more than 12,000 movies.

The lab, about two-thirds the size of a football field, is a data factory for AI-assisted drug discovery and development in Monrovia, California. It’s part of a wave of new companies and startups trying to use AI to produce more effective drugs, faster.

Companies are using the new technology — which learns from vast amounts of data to generate answers — to try to remake drug discovery. They are shifting the field from painstaking artisanal craft to more automated precision, a shift driven by AI that learns and gets smarter.

“Once you have the right kind of data, AI can work and be done really, really well,” said Jacob Berlin, co-founder and CEO of Terray.

Most of the early business uses of generative artificial intelligence, which can produce everything from poetry to computer programs, have been to help take the drudgery out of routine office tasks, customer service and writing code. However, drug discovery and development is a major industry that experts say is poised for an AI makeover.

AI is a “once-in-a-century opportunity” for the pharmaceutical business, according to consulting firm McKinsey & Company.

Just as popular chatbots like ChatGPT are trained with online text, and image generators like DALL-E learn from large numbers of photos and videos, AI for drug discovery relies on data. And it’s highly specialized data—molecular information, protein structures, and measurements of biochemical interactions. AI learns from patterns in the data to suggest potentially useful drug candidates, like matching chemical keys to the right protein blocks.

Because AI for drug development is powered by accurate scientific data, toxic “hallucinations” are much less likely than with more extensively trained chatbots. And any potential drug must undergo extensive testing in laboratories and clinical trials before it can be approved for patients.

Companies like Terray are building large high-tech labs to generate information to help train AI, which enables rapid experimentation and the ability to identify patterns and make predictions about what might work.

Generative AI can then digitally design a drug molecule. This design is translated, in a high-speed automated laboratory, into a physical molecule and tested for its interaction with a target protein. The results – positive or negative – are recorded and fed back into the AI software to improve its future design, speeding up the overall process.

While some AI-developed drugs are in clinical trials, it is still early days.

“Generative artificial intelligence is transforming the field, but the drug development process is messy and very human,” said David Baker, a biochemist and director of the Institute for Protein Design at the University of Washington.

Drug development has traditionally been an expensive, time-consuming, or doomed endeavor. Studies of the cost of designing a drug and navigating clinical trials to final approval vary widely. But the total expenditure is estimated at an average of 1 billion dollars. It takes 10 to 15 years. And nearly 90 percent of candidate drugs that enter human clinical trials fail, usually for lack of efficacy or unanticipated side effects.

New AI drug developers are trying to use their technology to improve those odds, while cutting time and money.

Their most consistent source of funding comes from pharmaceutical giants, which have long served as partners and bankers for smaller research ventures. Today’s AI drugmakers are typically focused on speeding up the preclinical stages of development, which have conventionally taken four to seven years. Some may try to go to clinical trials themselves. But this phase is where the big pharmaceutical corporations usually take over, running the expensive human trials, which can take another seven years.

For established drug companies, the partner strategy is a relatively low-cost route to exploiting innovation.

“For them, it’s like getting an Uber to take you somewhere instead of having to buy a car,” said Gerardo Ubaghs Carrión, a former biotech investment banker at Bank of America Securities.

Major pharmaceutical companies pay their research partners for achieving milestones towards drug candidates, which can amount to hundreds of millions of dollars over the years. And if a drug is eventually approved and becomes a commercial success, there is an income stream from royalties.

Companies like Terray, Recursion Pharmaceuticals, Schrödinger and Isomorphic Labs are pursuing breakthroughs. But there are, in general, two different paths – those that are building large laboratories and those that are not.

Isomorphic, the drug discovery from Google DeepMind, the tech giant’s central AI group, thinks that the better the AI, the less data it needs. And it’s betting on its software prowess.

In 2021, Google DeepMind released software that accurately predicted the shapes into which strings of amino acids would fold as proteins. These three-dimensional shapes determine how a protein works. This was a boost to biological understanding and useful in drug discovery, as proteins direct the behavior of all living things.

Last month, Google DeepMind and Isomorphic announced that their latest AI model, AlphaFold 3, can predict how molecules and proteins will interact – a further step in drug design.

“We’re focusing on the computational approach,” said Max Jaderberg, head of AI at Isomorphic. “We think there’s a huge amount of potential to be unlocked.”

Terray, like most drug development startups, is a byproduct of years of scientific research combined with the latest developments in AI.

Dr. Berlin, the chief executive, who earned his Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech, has followed advances in nanotechnology and chemistry throughout his career. Terray grew out of an academic project started more than a decade ago at the City of Hope cancer center near Los Angeles, where Dr. Berlin had a research group.

Terray is focusing on developing small-molecule drugs, essentially any drug a person can take in a pill like aspirin and statins. The pills are convenient to take and cheap to make.

Terray’s sleek labs are a far cry from the old days in academia, when data was stored in Excel spreadsheets and automation was a distant goal.

“I was the robot,” recalls Kathleen Ellison, a co-founder and senior scientist at Terray.

But by 2018, when Terray was founded, the technologies needed to build its industrial-style data lab were advancing rapidly. Terray has relied on advances from outside manufacturers to make the micro-scale chips that Terray designs. Its labs are filled with automated equipment, but almost all of it is custom—made possible by advances in 3-D printing technology.

From the start, the Terray team realized that AI would be essential to understanding its data reserves, but the potential for generative AI in drug development only became apparent later – albeit before ChatGPT became a hit in 2022.

Narbe Mardirossian, a senior scientist at Amgen, became Terray’s chief technology officer in 2020 — in part because of his wealth of data generated by the lab. Under Dr. Mardirossian, Terray has established its own data science and AI teams and created an AI model for translating chemical data into mathematics and back again. The company has released an open source version.

Terray has partnership agreements with Bristol Myers Squibb and Calico Life Sciences, a subsidiary of Alphabet, Google’s parent company, that focuses on age-related diseases. The terms of these agreements are not disclosed.

To expand, Terray will need funding beyond its $80 million venture funding, said Eli Berlin, Dr.’s younger brother. Berlin. He left a job in private equity to become the start-up’s co-founder and chief financial and operating officer, convinced the technology could open the door to a profitable business, he said.

Terray is developing new drugs for inflammatory diseases, including lupus, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. The company, said Dr. Berlin expects to have drugs in clinical trials by early 2026.

The drug-making innovations of Terray and his colleagues may speed things up, but only so much.

“The ultimate test for us and the field in general, is whether in 10 years you look back and you can say that the clinical success rate has greatly increased and we have better medicines for human health,” said Dr. Berlin.

#revolutionizing #drug #development

Image Source : www.nytimes.com